Doing Nothing

A month ago, I started having headaches. While some days I only felt a slight disturbance at the back of my head, I also experienced severe pains. At times I could feel my heart pounding inside my skull. I delayed going to the doctor’s office, although it’s been going on for a few weeks—until came a night when I feared my life. I started showing specific symptoms of having a stroke. I immediately called an Uber and went to an emergency room in the middle of the night. It was my first ER experience in a country where I don’t speak the native language. I did not know whether I would explain myself, but luckily, everyone I talked to was proficient in English—including the ER doctor who listened to my whole story and suspected the high stress as the root cause of my symptoms.

What happened next was the relief surrounding my body and my mind. Only then was I able to look back at those few weeks. Coming from Germany, we were going to spend a month in Turkey with our families, thus were preparing ourselves to fly multiple times in the middle of a pandemic. Our daughter was going through a growth spurt, and she was experiencing sleep regression, waking us all up—plus getting sick for the first time right before the flight. Raising a kid without much help in a foreign country, the chores were also our responsibility at all times. Working full-time and not socializing for several months added more pressure on our shoulders. I was always busy with something, either doing or thinking about something, due to many uncertainties. I was stressed, and I couldn’t even get the time to do anything to ease it.

While life can make us busy at all times, most of us are also fortunate enough to find time for leisure. Yet whenever we find ourselves doing nothing, we immediately react and get ourselves busy again. There is always a thing or two to finish. If not, our screens are always within arm’s reach for our endless entertainment. There is a steady input streaming into our brains. Now more than ever in human history, we can’t stay doing nothing because it seems counter-productive. Reality argues otherwise, as history reminds us time and again. A well-known example about Newton and the apple tree, the one perhaps we all know, shows how the law of gravitation occurred to him. William Stukeley recalls in his memoirs:

[…] on 15 April 1726 I paid a visit to Sir Isaac, at his lodgings in Orbels buildings, Kensington: din'd with him… after dinner, the weather being warm, we went into the garden, & drank thea under the shade of some appletrees, only he, & myself. amidst other discourse, he told me, he was just in the same situation, as when formerly, the notion of gravitation came into his mind. "why should that apple always descend perpendicularly to the ground," thought he to him self: occasion'd by the fall of an apple, as he sat in a contemplative mood […]1

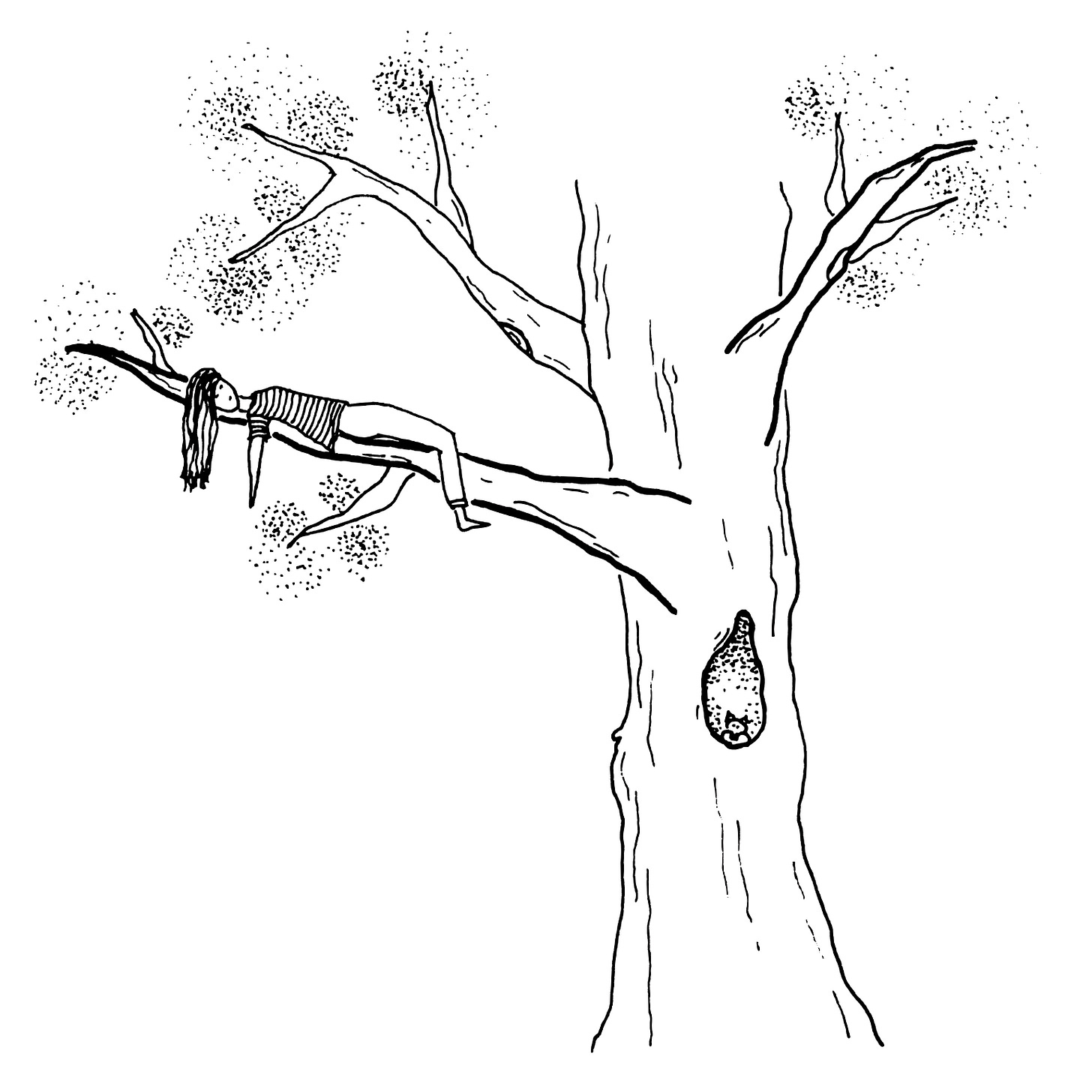

Artist: Gülfemin Buğu Tekcan — cosmodotart

What Isaac Newton experienced is idleness-induced creativity and innovation. Andrew Smart, the author of the book Autopilot, discusses that the human brain is the only system we know that can innovate. He adds that “the brain seems to need things like freedom, long periods of idleness, positive emotions, low stress, randomness, noise, and a group of friends with tea in the garden to be creative,”2 referencing Isaac Newton’s eureka moment on the gravitation. When we leave the critical parts of our brains unattended by relaxing in the garden, observing a piece of art, or just laying down listening to our favorite music, our brains take this opportunity to clean up the accumulated mess and leaving only the essential bits and pieces.

Following the analogy of cleaning up the mess, we can also conclude that our brains keep working even though we stay idle. It may work even harder by connecting the dots, finding patterns, and solving the problems you could not answer while trying your best to solve them. The creative genius Lin-Manuel Miranda3 argues that the good ideas don’t come when you are doing a million things, but when you’re in the shower or playing with your kid or taking a walk.4 “Many esteemed philosophers, from Kierkegaard to Thoreau, held their daily walk as something sacred, the key to generating new ideas.”5

I am not sure whether it was easier to be creative and come up with solutions to complex problems before the industrial revolution. While we have our screens for the last couple of decades, we started renting our time to the production of industrialized goods slightly more than 250 years ago6—and it’s nothing compared to the entire human history. We need many more generations and mutations for our brains to catch up being busy all the time. From an evolutionary perspective, we are still the hunter-gatherers in the jungle full of dangers. “It is crucial to be able to respond to the moment,” says Andrew Smart, since our survival may depend on this ability. “However,” he adds, “if that moment becomes every minute of every day of every month of every year, your brain has no time left over to make novel connections between seemingly unrelated things, find patterns, and have new ideas.”7

On top of the creative process, we can extract one more fact from human evolution. Smart argues that our brains are almost identical to the brains of Cro-Magnon, which researchers believe that their idleness caused the creative explosion in human development. In biological terms, “once basic needs are met—food, shelter, protection from elements and adversity—it is no longer necessary to work,” which also legitimizes the ancient Greeks considering “anyone who had to work to make a living was considered a slave.”8 Many manuscripts are praising doing nothing like Paul Lafargue’s The Right to be Lazy and Bertrand Russell’s In Praise of Idleness. I also argue that technology advancements will eventually scrape most of the manual work humans need to do and leave the ones that need our creative parts.

While concluding the post, I also want to criticize the politicians promising more jobs. Whenever I hear such guarantees at election times, my skepticism skyrockets. It is not easy to create millions of jobs that would provide value to the whole society in a short amount of time.9 They are the jobs created mainly in the service industry where the human muscle is necessary and not the brain. Those are the jobs that would exhaust the individuals while delaying the subsequent creative explosion. While the economics of the advancement is yet to be concluded, I long for the future where humans stay idle by default—but work to create.

How much leisure time do you give yourself every week? Do you think you could live in a world where “doing nothing” is the default mode? Let me know in the comments.

PS: I added many references from Andrew Smart’s book Autopilot in this post. I highly recommend the book as what I learned from him has stuck with me for the last seven years.

Universal Gravitation from the Physics Hypertextbook containing William Stukeley’s memoirs from 1752.

Autopilot: The Art and Science of Doing Nothing by Andrew Smart

Lin-Manuel Miranda is an American actor, singer, songwriter, rapper, director, producer, and playwright. He created and starred in the Broadway musicals In the Heights and Hamilton. His awards include a Pulitzer Prize, three Tony Awards, three Grammy Awards, an Emmy Award, a MacArthur Fellowship, and a Kennedy Center Honor in 2018.

How Googlers Avoid Burnout (and Secretly Boost Creativity) by Brad Stulberg and Steve Magness on Wired

Peak Performance: Elevate Your Game, Avoid Burnout, and Thrive with the New Science of Success by Brad Stulberg and Steve Magness

“The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Europe and the United States, in the period from about 1760 to sometime between 1820 and 1840.” from Industrial Revolution on Wikipedia

Autopilot: The Art and Science of Doing Nothing by Andrew Smart

Autopilot: The Art and Science of Doing Nothing by Andrew Smart

“Still, it is true that governments can create jobs. It's just that they're almost never the jobs that actually help the economy. The government can hire 20 million people to move piles of dirt around or to just sit around if it wants. That will "create jobs." But it won't be good for the economy, because those people are not productive for the economy. They won't be adding value or producing something of value that expands the economy.” from Politicians, Innovation & The Paradox Of Job Creation by Mike Masnick

"I long for the future where humans stay idle by default—but work to create." All of us do I believe :) Great piece of writing for my Sunday morning. Thanks.