Procrastination

I write weekly on Sustainable Productivity for the past three months. I enjoy the act of writing as well as the reading and the research I’m putting in every week. I like how the post shapes up when editing the text. I love the dot-art Gülfemin is drawing for each article. I also like the outcome: When I finish the week’s article, I feel a sense of accomplishment because what I concluded is not just an article; it’s also a planned step I took towards my goal of sustainable productivity.

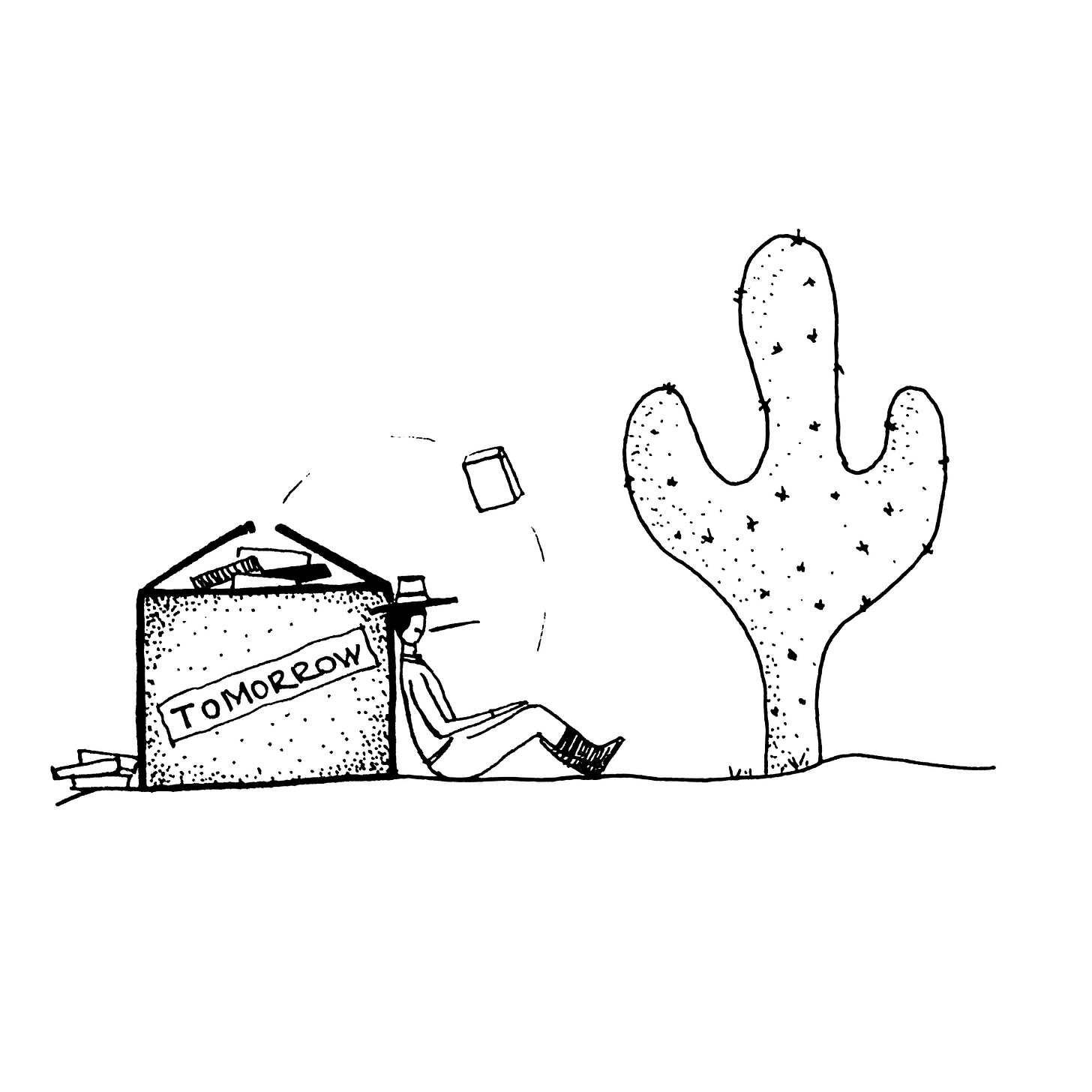

Yet, every week, I’m facing a dilemma. I want to complete the week’s writing way before the publishing day. And every day, I say to myself, “I will do it tomorrow.” This postponing goes on until we arrive at the last night before the publishing day, and only until then I sit down and focus until the text is complete. What I’m experiencing is not something unique, and the word describing this is a big one: Procrastination. The word comes from Latin, which we can decompose as “forward” and “of tomorrow”1. It is the action of delaying something—just like I’m delaying the act of writing up until the last possible date.

When I try to look at the times I procrastinate, I can find a couple of common scenarios. For example, I see the act of writing as a big task. It’s not as easy as sitting down and crunching some words together. I know what I’m going to write about that week because I already planned the year. However, I still need to find a point of view to write from. Then I need to plan the structure of the text and whether I’m going to add a personal story at the beginning. While I’m writing, I need to collect my sources and refer to them appropriately. I need to make my point on solid ground and then conclude with a high note. Then I go back and edit and reread the whole text a couple of times until I’m satisfied. It’s a lot of work—no wonder I postpone it to tomorrow.

Artist: Gülfemin Buğu Tekcan — cosmodotart

Apart from being intimidated by the amount of work needed, sometimes I find myself fearing the consequences. What if I start working, only to realize that I don’t know anything about the subject? Or let’s say I put a lot of time into research and learn that what I know right has been wrong all along. Even if I successfully plan the article with beautiful references to achieve a meaningful conclusion, what if the resulting text comes out sub-optimal? Well, I learned this the hard way: Chasing perfection is only helpful if you settle with good enough.

The examples I’ve given above represent several so-called negative emotions led by fear. Surprisingly, that’s not a coincidence. Erhan Genç speculates that “Individuals with a higher amygdala volume may be more anxious about the negative consequences of an action—they tend to hesitate and put off things,”2 following the research he conducted at Ruhr-Universität Bochum. Amygdala, put simply, is a part of our brain performing a primary role in the processing of decision-making and emotional responses, including fear.3 If we can connect procrastination to our emotions, we can also suggest that we procrastinate not because of laziness but human biology—hence the procrastinators are not a subset; all humans are procrastinators to some degree.

If you find yourself surrounded by your emotions and cannot see a clear path to logical thinking, there might also be some good news. A peer-reviewed research article shows that mindfulness can help physically shrink the amygdala volume.4 Mindfulness training done over eight weeks may be sufficient enough to get the first results by fostering neuroplastic changes in cortico-limbic circuits responsible for stress and emotion regulation. I believe this revelation is enormous, especially for people getting affected by their emotion-driven decisions seriously.

Mindfulness aside, there are a couple of practical tactics I find helpful to challenge my inner procrastinator:

Divide & Conquer: If the task seems too big, dividing it into subtasks can get you out of that fear bubble. Finishing a task will give you a sense of accomplishment and get you going with the next one. Just be careful when dividing the task: The small task should be meaningful on its own so that you will have created value at the end of it. It should also be doable in a set time which brings me to my next tactic.

Timeboxing: It is a simple yet effective way to make progress. You set a fixed amount of work time, say 25 minutes, followed by a break, say 5 minutes. You turn off everything during work time as you should not do anything but work. The same goes for the break. After the 25 minutes is over, you immediately stop working, even though you did not finish the task you’ve been working on. A famous timeboxing technique is the Pomodoro Technique (opens video).

The tactics above help you begin working on the task. That’s why they are very efficient at solving the problems procrastination creates. Carleton University’s Tim Pychyl states that “Our research and lived experience show very clearly that once we get started, we’re typically able to keep going. Getting started is everything.”5

Until this point, we’ve only talked about how procrastination pulls you away from what you want to achieve. There is another side to this reality: Waiting can sometimes be good. Inherently I noticed this while working as a software engineer. Say you have a product you’re creating, and users complain about something. Waiting can provide you a higher ground on seeing all the complaints. You’ll see some of the complaints will be repeated by many users, and the others will just become noise in between. That’s how you can prioritize which problems to address. As with complaints, you could also get feature requests. If you wait for enough, you may also see that your users will not need those features at all.

While I’ve thought that I grasped the nature of procrastination, I wasn’t sure when I should wait and when I should act. Then I read Adam Grant’s bestseller Originals. He provided a good rule of thumb on when to procrastinate. While "procrastination is a vice for productivity, I've learned--against my natural inclinations--that it's a virtue for creativity," details Grant6. If what you’re working on requires you to get creative, procrastination makes sense. Because even though you’re not focused on the work, your brain is thinking, processing, connecting the dots even without you noticing sometimes. When you arrive at the point where you need to finish the task, you’ll already have made quite an arsenal to ace the whole work.

How big of a procrastinator are you? Do you have any memories that procrastination affected your life negatively? Did you have an experience where waiting was very beneficial for you? Let me know in the comments.

Bonus: Here is a fun TED Talk about procrastination by Wait but Why’s Tim Urban: Inside the mind of a master procrastinator.

Procrastination on Wikipedia

How brains of doers differ from those of procrastinators: A press release on The structural and functional signature of action control published in Psychological Science, 2018.

Dispositional Mindfulness Co-Varies with Smaller Amygdala and Caudate Volumes in Community Adults by Adrienne A. Taren, J. David Creswell, and Peter J. Gianaros

Why procrastination is about managing emotions, not time by Christian Jarrett on BBC Worklife

Here's the Counterintuitive Reason Why Adam Grant Says You Should Procrastinate More by Peter Economy on Inc.